Exterior View (2011), 11” x 15” Watercolor, Jay A. Waronker

Exterior View (2011), 11” x 15” Watercolor, Jay A. Waronker

south africa

Bloemfontein Progressive Synagogue (Completed in 1964) |

|

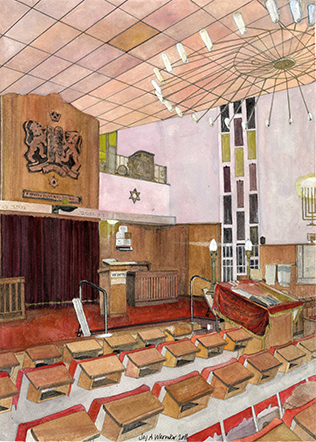

Interior View (2011), 11” x 15” Watercolor, Jay A. Waronker

|

Jews, mostly of German origin, first settled in the Free State of central South Africa, in what was then called the Orange River Sovereignty, in the 1840s. At that time, the Jews became part of the Sovereignty’s overall white population that did not exceed 4,000 people. In 1855, the Orange River Sovereignty became the Orange Free State, and during this period it was common to find at least one or two German Jewish families living in nearly every town and hamlet of the state. This small and dispersed Jewish community oversaw a large portion of the trade of the state along with pursuing other occupations and professions. Whereas in early years the scattered Jewish communities prayed in private homes or temporary facilities, in time they built dozens of small synagogues throughout the Free State. None of these other than one in Bloemfontein still operate as synagogues, some of the buildings have been repurposed to serve other functions, and others no longer stand as the land has been redeveloped or due to other factors, including fire.

In 1871, an annual Yom Kippur service was instituted in the home of a Jew living in Bloemfontein, the capital of the Orange Free State. Also in 1871, the first Jewish funeral was held in the Orange Free State, and two years later marriages by Jewish rites were legalized. The small Jewish population that numbered forty-one people by the end of the 1870s grew in the 1880s and early 1890s to include new arrivals from Eastern Europe. By 1890, with one hundred fifty Jews living in Bloemfontein, a congregation was established. A rabbi from Kimberly, South Africa came to town on a rotating basis to officiate over events and lead prayer services. During the period, the Jews of Bloemfontein used the Free Mason’s Building for prayer services, and later they shifted to private homes or rented halls.

At the turn of the century, land for the building of a proper synagogue was purchase by the local Jews for the building of their first proper synagogue. Around that time Bloemfontein’s Jewish population numbered around 1,600 people. Construction on the synagogue began in 1903, and the building was consecrated in March 1904. Among those attending the dedication ceremony was the lieutenant-governor; the executive council, and the justices of the Free Orange State. This building continued to serve the congregation until the 1940s when a far larger structure was constructed on a new site immediately to the north of the city center (refer to this website about this building). Today the site of Bloemfontein’s first synagogue contains commercial buildings, and there is nothing on the property that acknowledges what once stood there.

In the early 1960s, Jews wishing to embrace the Progressive Movement broke away from their fellow Orthodox members and established their own congregation. Within a short time, these Progressive Jews built their own synagogue, and the Orthodox Jews continued to base themselves out of the earlier building. Local Jewish architect Geoffrey L. Cohen was commissioned by the Bloemfontein Progressive Jewish community to design the congregation a progressive Modern synagogue on a parcel of land set within a sprawling residential community of single family houses to the east of the downtown business core. The bold design, which featured a double-height sanctuary with foyer and restrooms, was laid out to accommodate an anticipated addition to house a social hall, offices, classrooms, and a kitchen. These support and secondary spaces, not part of the architect’s original scope of work, were added in a more conservatively-designed fashion some years after completion of the sanctuary in 1964.

The triangular site of the synagogue property, with its apex facing north-east, and with the effective area reduced to less than half by the application of building lines, helped direct the overall funnel-shaped form of the architecture and the how it was placed on the ground. The sanctuary space is contained within a two-story dramatic geometric shape finished in white exterior plaster. This modern if not daring form, which contrasts if not be considered alien to more conventionally-designed mid-century modern houses in the neighborhood, is a stand-out object in its context. The building is surrounding by open green space with mature trees and a low retaining wall finished in the same exterior plaster as the building. Essentially a funnel in response to the site, the building’s apex is not a point but a graceful curve. The building massing is solid and smooth except for some small roof scuppers and four vertical strips on each side of the form. These breaks contain panels of windows, some colored. As the Ark had to be placed at the north towards Jerusalem as per Jewish custom, it was positioned at the apex.

The progression from approaching from the outside and walking into the inside of the synagogue was an important consideration of the architect. Cohen designed a sequence of spaces that involved one passing under what was originally a free floating canopy into a paved open court, thence into a formal entrance foyer which led into the synagogue proper. In more recent years, the graceful entrance canopy, which apparently leaked, was comprised with a heavier and less visually interesting sloped roof. The main approach is at a high point along Paul Roux Street, which is lined with single family houses, and the building is hidden until one is virtually upon it. The synagogue’s entrance is around the corner on Dickie Clark Street, a less traveled thoroughfare that is also completely residential.

The triangular site of the synagogue property, with its apex facing north-east, and with the effective area reduced to less than half by the application of building lines, helped direct the overall funnel-shaped form of the architecture. The sanctuary is contained within this triangular parcel of land, and it is a two-story dramatic form finished in white plaster walls with a stain-wood wainscot. These walls are broken by four vertical strips on each side of the room that contain a grid panel of windows, some of colored glass. Displayed on walls are dedication or ceremonial panels. Towards the apex is where the ark and ner tamid (eternal lamp) are placed, and behind the wall of the Ark is a considerable amount of seemingly wasted space. Above the ark is an oversized panel featuring commandant tablets flanked with two lions. This stained-wood panel covers some of the upper level space designed for the choir.

Other architectural features of the sanctuary include fixed theatre-like seats upholstered in red leather and with prayer book ledges, a centrally-positioned wooden bimah (table where the Torah is read) draped in a deep red velvet, solid red carpeting, seating for the rabbi and officers of the synagogue flanking the Ark, a ceiling finished in acoustical tiles, and a very large multiple-armed metal chandelier in the center of the space. Behind the men’s seating is the mechitza (partition screen) added by the Orthodox Jews when they bought and repurposed the building from the Progressive Jewish Congregation. This unusual screen is made out of a wood and metal frame with angled glass slats. What is somewhat usual about this sanctuary since this change is that the room is entered to the rear alongside the women’s seating area. Only after passing the rows of seats for the women screened by a wooden partition does the main space of the sanctuary come into view. This spatial arrangement was not intentional but made necessary when the room was retrofitted to serve the needs of its Orthodox Jews. Today the sanctuary contains some one hundred twenty seats, although due to the dwindled community many go occupied during regular prayer services.

Soon after the synagogue was completed, Cohen’s design and photographs of the building was published in a leading South African architectural journal. This building served the Bloemfontein Progressive Jewish community until the 1990s. At that time, as a result of the uncertain conditions of post-apartheid South Africa, many White South Africans that included Jews emigrated. With its congregation much declined, their large building was no longer needed, and the Orthodox Jews purchased the smaller building realized by the now-defunct Progressive Jewish Congregation. After retrofitting its space to serve their needs, the Orthodox Jews began operating out of the somewhat repurposed building. The community, although small, continues to use it today, and visitors are especially welcome.